The article below by J. Calmard “The Anglo-Persian War of 1856-1857” was first published in the Encyclopedia Iranica on December 15, 1985 and last updated on August 5, 2011. This article is also available in print in the Encyclopedia Iranica (Vol. II, Fasc. 1, pp. 65-68).

Kindly note that the photos/illustrations and accompanying captions inserted below do not appear in the original Encyclopedia Iranica article.

========================================================

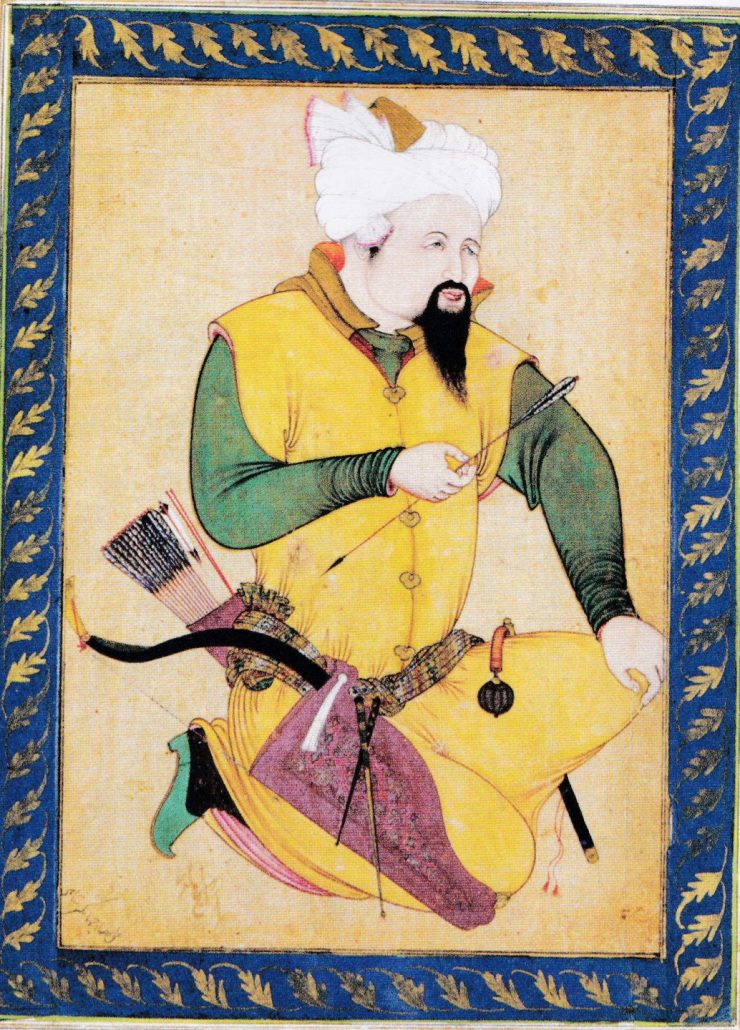

Following their defeat in the Russo-Persian wars of 1219-28/1804-13 and 1242-44/1826-28, the Qajars, tried to compensate for their losses by reasserting Persia’s control over western Afghanistan. Attempts to bring the principality of Herat under their rule in 1249/1833, 1253-55/1837-39, and 1268/1852 were strongly resisted by the British: If Herat were in Persian hands, the Russians—whose influence was paramount at the Persian court—would directly threaten India. In Afghanistan, Persian ambitions complicated internal struggles for the control of the “Khanates” of Kabul, Qandahār, and Herat. Since the 1820s, Kabul, and then Qandahār, had been ruled by the Bārakzī or Moḥammadzī, while Herat was held by the Sadōzī. In 1258/1842 Kāmrān Sadōzay was murdered by his vizier, Yār Moḥammad Khan. When the latter died in 1851, his son and successor, Ṣayd Moḥammad Khan, asked Nāṣer-al-dīn Shah Qāǰār for assistance against the Bārakzay amirs, in Kabul, and Kohandel Khan in Qandahār. In spite of warnings from the British minister in Tehran, Colonel Sheil, the Persians moved into Herat the next spring, but faced with British threats to break diplomatic relations and reoccupy Ḵārg island, the shah withdrew his troops (G. H. Hunt, Outram and Havelock’s Persian Campaign, London, 1858, pp. 149f.; P. P. Bushev, Gerat i anglo-iranskaya voĭna, Moscow, 1959, pp. 43f.), agreeing not to send them to Herat again unless it was threatened from the east and not to interfere in Herat’s internal affairs (engagement of 15 Rabīʿ II 1269/25 January 1853: see parts regarding ḵoṭba and coinage in C. U. Aitchison, A Collection of Treaties, Engagements, and Other Sanads Relating to India and Neighbouring Countries, Delhi, 1933, XIII, no. XVII, pp. 77f.; see also Hunt, Outram, pp. 155f.; Bushev, Gerat, pp. 44f.).

![1-Sir Charles Augustus Murray]() The bumbling diplomat? An 1851 photo of a seated Charles Augustus Murray (1806-1895) prior to his diplomatic mission to Iran (Source: Public Domain). As soon as he arrived as British ambassador to Tehran in 1854, it became clear that he and Nasseredin Shah (r. 1848-1896), monarch of Qajar Iran, disliked each other. Murray’s inept diplomacy helped contribute to the rupture of Anglo-Iranian relations.

The bumbling diplomat? An 1851 photo of a seated Charles Augustus Murray (1806-1895) prior to his diplomatic mission to Iran (Source: Public Domain). As soon as he arrived as British ambassador to Tehran in 1854, it became clear that he and Nasseredin Shah (r. 1848-1896), monarch of Qajar Iran, disliked each other. Murray’s inept diplomacy helped contribute to the rupture of Anglo-Iranian relations.

In 1853, Sheil was succeeded in Tehran by Charles Augustus Murray, who had no Indian experience and has been strongly criticized by both contemporaries and historians (e.g., Sir D. Wright, The English amongst the Persians, repr. London, 1977, p. 23); his troubles in Tehran were among the causes of the Anglo-Persian war. Before his arrival the shah knew him to be on friendly terms with his old enemies, the rulers of Egypt and Masqat, while an article published in the London Times predicted that he would soon force the shah to accept British policy regarding Herat. Moreover, he came “with neither an expected loan nor a draft defensive treaty nor presents,” to the disappointment of the court (ibid.). His lack of experience in Eastern diplomacy had disastrous results. Soon after his arrival, he became embroiled in a dispute with the ṣadr-e aʿẓam over the appointment of a former government official to the British Mission in Shiraz; the confrontation escalated to the point where the official’s wife, the sister of one of the shah’s wives, was imprisoned, and both Murray and his senior assistant were accused of improprieties with her. In a rescript to his ṣadr-e aʿẓam, Mīrzā Āqā Khan Nūrī, (later annexed to the Treaty of Paris of 1857), the shah called Murray stupid, ignorant, and insane (ibid., p. 24); copies of the document were then sent to the foreign missions in Tehran, who were also informed by the ṣadr-e aʿẓam of the alleged offense. Murray was authorized by his government to break off relations with Persia; mediations by the Ottoman chargé d’affaires and the French minister were of no avail (Hunt, Outram, pp. 160f.; Bushev, Gerat, pp. 55f.). On 20 November 1855, Murray struck down his flag; he left Tehran for Tabrīz on 5 December and moved to Baghdad in May. The British consul, R. W. Stevens, remained in Tehran, where he was the only link with the Foreign Office and the India Board till September, 1856.

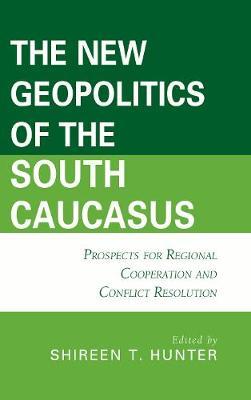

In Afghanistan, Persia’s threatening attitude caused Dōst Moḥammad to conclude a treaty of perpetual peace and friendship with Britain (30 March 1855; see Aitchison, A Collection, pp. 237f.). The ruler of Herat, Ṣayd Moḥammad, was deposed and killed, and in September-October, 1855, Moḥammad Yūsof Sadōzay, who was regarded as a Persian nominee, seized power there (Ḥ. Sarābī, Maḵzan al-waqāyeʿ, ed. K. Eṣfahānīān and Q. Rowšanī, Tehran, 1344 Š./1965, introd., p. 23). Despite the engagement signed by the shah in 1853, a Persian army soon marched toward Herat. Afraid of being crushed between the shah and Dōst Moḥammad, who had taken Qandahār in August, Moḥammad Yūsof tried to temporize, but Ḥosam-al-salṭana Solṭān Morād Mīrzā, commander of the Persian force, was ordered to push forward with all speed. In desperation, Moḥammad Yūsof hoisted the British flag at Herat, only to be treacherously seized and sent as a prisoner to the Persian camp by his vizier, ʿĪsā Khan (M. J. Ḵormūǰī, Ḥāqāʾeq al-aḵbār-e Nāṣerī, ed. H. Ḵadīvǰam, Tehran, 1344 Š./1965, pp. 176f.). The Persians began to capture forts and other sites around Herat as far as Farāh, but Persian troops who managed to invade Herat with the complicity of local Shiʿites were driven out by a bloody uprising (ibid., pp. 181f.). In renewed fighting ʿĪsā Khan hoisted the British flag and even offered Herat to the British crown in return for aid (J. F. Standish, “The Persian War of 1856-1857,” Middle Eastern Studies 3, 1966, pp. 28-29). Under threats from the shah, Solṭān Morād increased his pressure against Herat, which fell to the Persians at the end of October, 1856.

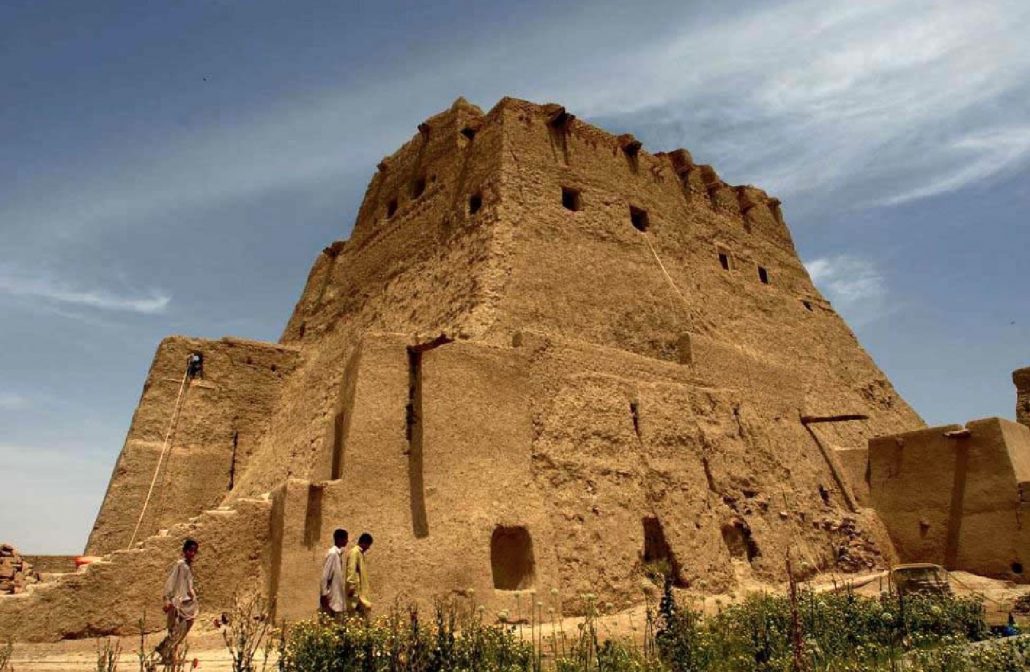

![2-Citadel of Herat 1880s]() The citadel of Herat in 1885 (Source: qdl.qa).

The citadel of Herat in 1885 (Source: qdl.qa).

In the meantime, the diplomatic scene had changed since the end of the Crimean War in April, 1856: Russia could consider further progress toward India, and France was no longer Britain’s ally (Standish, “The Persian War,” p. 30). In Istanbul, the Persian chargé d’affaires tried to settle diplomatic difficulties by negotiations with the British minister Lord Stratford de Redcliffe (interviews of January and April, 1856; see Hunt, Outram, pp. 167, 178-79). In July, the shah sent Farroḵ Khan Amīn-al-molk (later Amīn-al-dawla) Ḡaffārī on an extraordinary embassy to Paris. Meeting in Istanbul with Lord Stratford de Redcliffe at a time when the British were preparing a military action against Persia (Sarābī, Maḵzan, introd., pp. 34f., text, pp. 117f.), Farroḵ Khan was presented with an ultimatum insisting on the dismissal of the ṣadr-e aʿẓam; finally, he accepted the terms of another, more conciliatory, ultimatum sent by Lord Stratford de Redcliffe to the Persian chargé d’affaires during the summer (Hunt, Outram, pp. 181-84, 189). With British authority divided between Britain and India and contradictory advice being given by men in the field (Stevens in Tehran, Edwardes in Peshawar), the Indian government was confused (Standish, “The Persian War,” pp. 26-27, 31-33). From Baghdad, Murray continued to send Foreign Secretary Clarendon proposals for a punitive expedition against Persia, yet overtures made to secure Dōst Moḥammad’s cooperation (Treaty of 26 January 1857 in Aitchison, A Collection, pp. 238f.) were of no avail (Sir P. Sykes, A History of Persia, 3rd ed., 1915, repr. London, 1969, II, p. 349). In both Persia and India, first-rank officials were opposed to war (Sarābī, Maḵzan, introd., p. 30; H. C. Wylly, “Our War with Persia in 1856-57,” United Service Magazine, London, March 1912, pp. 642f.).

After the capture of Herat, British agents were expelled from or left Persia; the last to go was Felix Jones, the political resident at Bushire, who left in November, 1856, only four days before the arrival there of three English warships (Fasāʾī, I, p. 313). To avoid public outcry against Palmerston’s government, the British declared war from Calcutta, on 1 Novernber 1856 (Wright, The English, p. 56). After considering direct action on Herat through Afghanistan or from Bandar ʿAbbās, they decided to operate in the Persian Gulf (Sykes, History II, pp. 349f.). A naval expedition under the command of Major-General Stalker occupied Ḵārg island on 4 December; on 10 December Bushire surrendered and was placed under British administration (Fasāʾī, pp. 313f.). On 27 January 1857, Sir James Outram landed at Bushire and took command.

![Anglo-Persian War-Khorramshahr]() Captured territory in the Khorramshahr area on the mouth of the Persian Gulf in 1857; note British flag (Source: Antiqua Print Gallery).

Captured territory in the Khorramshahr area on the mouth of the Persian Gulf in 1857; note British flag (Source: Antiqua Print Gallery).

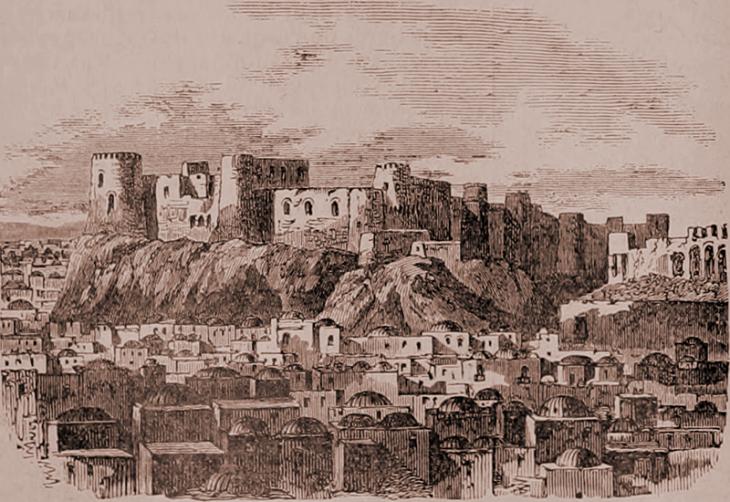

On the Persian side, ǰehād was proclaimed and changes made in the army leadership, but the Bushire campaign was ill prepared. Taking the initiative, Outram marched on the main body of Persian troops encamped at Borāzǰān, about 100 km northeast of Bushire. The British column occupied Borāzǰān on 5 February, bur the Persian army had already retreated to the north, leaving behind equipment and weapons. After destroying the Persian arsenal, the British marched back to Bushire but were met with a combined attack from the Persian regulars and the Qašqāʾī cavalry on the night of 7 February. At dawn, the British cavalry and artillery look the offensive and inflicted a massive defeat on the Persians (who lost 700 men to 16 on the British side; see Outram’s report in The Annual Register, 1857, p. 444; Sir J. Outram, Lieutenant-General Sir James Outram’s Persian Campaign in 1857, London, 1860, pp. 33-35; Wylly, “Our War,” p. 648; different figures given by Fasāʾī, I, p. 317; A. D. Hytier, ed., Les dépêches diplomatiques du Comte de Gobineau en Perse, Paris and Geneva, 1959, p.71, n. 95, et al.).

Despite Ottoman objections, the next operation was directed against Moḥammera (later Ḵorramšahr), which had been made over to Persia by the Treaty of Erzurum in 1847 and strongly fortified later on. In a purely naval battle fought on 26 March, Outram and Henry Havelock (who had arrived in reinforcement with his division) pounded the shore batteries with mortars. After some two hours’ fire, the shore batteries were silenced; troops were landed “only to find that the Persian force had fled, after exploding their chief magazine, but leaving everything behind them” (Wylly, “Our War,” p. 650; see also C. D. Barker, Letters from Persia and India 1857-1859, London, 1915, pp. 26f.). An armed flotilla sent up the Kārūn river reached Ahvāz on 1 April and returned to Moḥammera two days later. Military action at Moḥammera ended on 5 April when news was received that peace had been signed on 4 March.

![Qajar Zanbourak unit]() A case of obsolescence: a Qajar Zanbourak (small cannon fitted on camel) military unit (Source: Persiawar.com). Iran’s military state by the 1850s was one of poor leadership, disorganization, low morale, poor training and substandard military equipment.

A case of obsolescence: a Qajar Zanbourak (small cannon fitted on camel) military unit (Source: Persiawar.com). Iran’s military state by the 1850s was one of poor leadership, disorganization, low morale, poor training and substandard military equipment.

In fact, the Persian government had sued for peace directly after the capture of Bushire. Through the mediation of Napoleon III and his foreign minister, Count Walewski, Farroḵ Khan managed to start negotiations with Lord Cowley, British minister in Paris. This led to the signature of the Treaty of Paris on 4 March 1857, with ratifications exchanged at Baghdad on 2 May 1857. Persia was obliged to relinquish all claims over Herat and Afghanistan, while Britain was to serve as arbiter in any disputes between Persia and the Afghan states (article 6). British consular authorities, subjects, commerce, and trade were to be treated on a “most favored nation” basis (article 9). In a separate note to the treaty, the terms of Murray’s return to Tehran were set out in “humiliating detail” (Wright, The English, p. 24). Otherwise, no guarantees, no indemnities, and no concessions were exacted; there was no demand for the ṣadr-e aʿẓam’s dismissal (Standish, “The Persian War,” p. 39), and the shah’s note of December 1855 insulting Murray was even annexed (see Aitchison, A Collection XIII, no. XVIII, pp. 81-86).

Although he was received in Tehran in July, 1857, with the agreed ceremonial, Murray was not to see the end of his troubles till the fall of the ṣadr-e aʿẓam Mīrzā Āqā Khan Nūrī (20 Moḥarram 1275/30 August 1859). Count de Gobineau, the French chargé d’affaires in Tehran, who had taken charge of British interests, complained bitterly about the problems caused by the British protégés (Gobineau, Les dépêches, pp. 32f.). Murray complained in turn abort the lack of support these got from the French Legation (ibid., p. 93, n. 136 and Murray’s dispatches in FO/60/230 and 231). Both in 1855 and 1857, Murray complained about the eviction of the British Legation from the seats of honor it had formerly occupied on official ceremonies, including taʿzīa (passion play) performances (see J. Calmard, “Le mécénat des représentations de taʿziye, II,” Le Monde iranien et l’Islam 4, Paris, 1976-77, pp. 157f., and Moḥarram Ceremonies and Diplomacy, in Qajar Iran, Edinburgh, 1983, pp. 213-28. But the main troubles arose from the necessity of enforcing the terms of the treaty. Although the last British troops were not withdrawn from Ḵārg island till the spring of 1274/1858, the main body had left the Persian Gulf for India at the outbreak of the mutiny (May-June, 1857; see Outram, Persian Campaign, pp. 321f.). In Herat, the Persians were slow in evacuating the area of Lāš-Jovayn (see Murray’s dispatches in FO/60/230); there were problems connected with minorities (e.g., Herat Jews imprisoned at Mašhad) and the settling of the reciprocal atrocities and exactions between Sunnites and Shiʿites which had taken place during the war (on Colonel R. L. Taylor’s mission to Herat see FO/60/218, 219, 220; Bushev, Gerat, pp. 155f.).

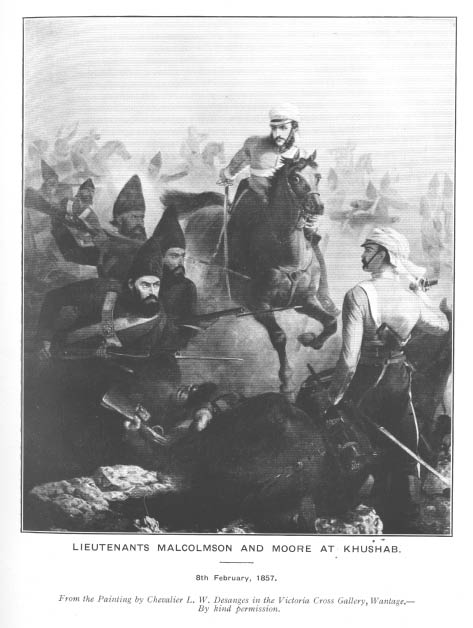

![Battle of Khosab]() The Battle of Khushab (February 8, 1857) as depicted on a British postcard which reads “Lieutenants Malcolmson and Moore at Khushab” (Source: Persiawar.com). The postcard is making specific reference to Captain J.G. Malcolmson, and Lieutenant A.T. Moore who ere awarded Victoria Crosses by the British Empire for their battlefield exploits during the Anglo-Iranian War. The British and Iranian sides were evenly matched in numbers (4600 British versus 5000 Iranians) at Khoshab, but the British held the technical edge in terms of military equipment, a factor which significantly contributed to their victory at Khushab in Iran’s Bushehr province.

The Battle of Khushab (February 8, 1857) as depicted on a British postcard which reads “Lieutenants Malcolmson and Moore at Khushab” (Source: Persiawar.com). The postcard is making specific reference to Captain J.G. Malcolmson, and Lieutenant A.T. Moore who ere awarded Victoria Crosses by the British Empire for their battlefield exploits during the Anglo-Iranian War. The British and Iranian sides were evenly matched in numbers (4600 British versus 5000 Iranians) at Khoshab, but the British held the technical edge in terms of military equipment, a factor which significantly contributed to their victory at Khushab in Iran’s Bushehr province.

In Herat, ʿĪsā Khan had been put to death on 6 Rabīʿ II 1273/4 December 1856; Moḥammad Yūsof met a similar fate at the hands of Ṣayd Moḥammad’s relatives (Ḵormūǰī, Ḥaqāʾeq, pp. 191, 229f.; R. C. Watson, A History of Persia . . . to the Year 1858, London, 1866, pp. 463f.). Before they withdrew, the Persians installed Solṭān Aḥmad Khan, the nephew and son-in-law of Dōst Moḥammad, as Herat’s ruler. Effectively a vassal to the Persian crown (though this was never officially proclaimed), he enjoyed de facto British recognition as well. He was overthrown by Dōst Moḥammad in May, 1863; until then the Persian government managed to keep control over Herat while adhering to the Treaty of Paris (Standish, “The Persian War,” p. 35).

The success of the British soldiers, more than a half of whom were Indian, was mainly due to technological superiority and new English rifles. Even so, British commanders faced the strain of barely sufficient means and lack of training. Three of them, Outram, Havelock, and John Jacob, were to become legendary Anglo-Indian figures, but the two service commanders committed suicide during the early stages of hostilities (Standish, “The Persian War,” p. 35; see also Barker, Letters, pp. 23f.). Disorganization on the Persian side is illustrated by the lack of enthusiasm for the ǰehād against the British preached by the ʿolamāʾ and Mīrzā Āqā Khan (see H. Algar, Religion and State in Iran, 1785-1906, Berkeley, 1969, pp. 154f.). Connections between the Persian war and the Indian mutiny remain inconclusive (Standish, “The Persian War,” p. 39). It should be also noted that repeated Persian claims of the necessity to pacify Khorasan from constant Turkman raids were considered by the British as a mere pretext for the seizure of Herat.

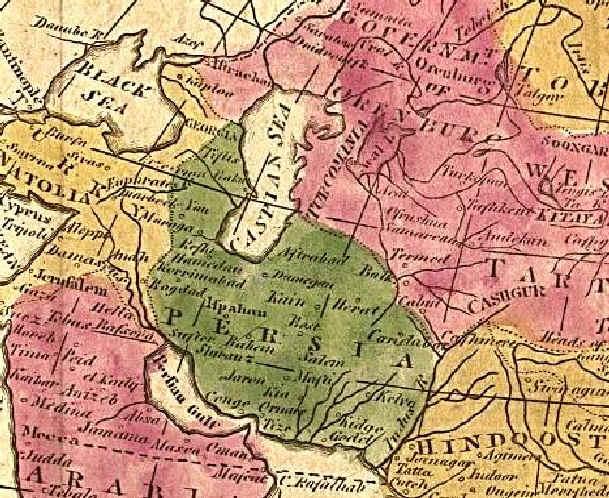

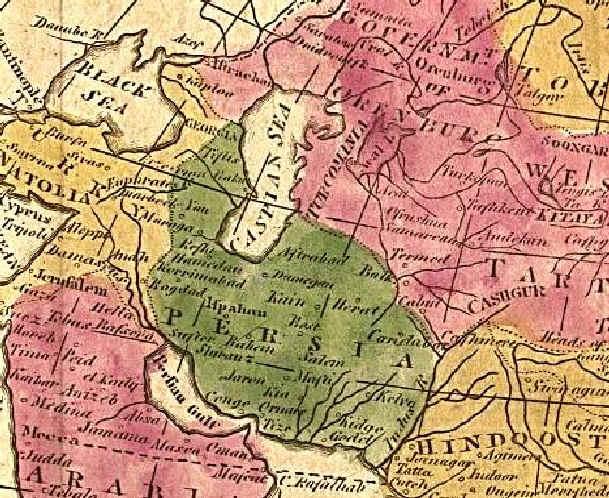

![Early 19th century Map of Iran]() Map of Iran in 1805 before her territorial losses in the Caucasus to Czarist Russia and the losses of Herat and Western Afghanistan due to British military actions. Just as the treaties of Golestan (1813) and Turkmenchai (1828) forced Iran to relinquish her territories in the Caucasus to Russia, so too did the Treaty of Paris (1857) force Iran to relinquish her territories in Afghanistan as per British objectives (Picture source: CAIS).

Map of Iran in 1805 before her territorial losses in the Caucasus to Czarist Russia and the losses of Herat and Western Afghanistan due to British military actions. Just as the treaties of Golestan (1813) and Turkmenchai (1828) forced Iran to relinquish her territories in the Caucasus to Russia, so too did the Treaty of Paris (1857) force Iran to relinquish her territories in Afghanistan as per British objectives (Picture source: CAIS).

It has often been said that Britain’s relations with Persia improved after the war. Although from the British standpoint this may be partially true, there was a widespread tendency among the Persians to consider the British as the main source of their troubles, and Anglophobia was also felt elsewhere. Although allied with the British in the Crimean War (1854-56) and the second opium war in China (l856-61)), the French were alarmed by British expansionism in the Persian Gulf (E. Flandin, “La prise d’Hérat et 1’expédition anglaise dans le Golfe Persique,” Revue des deux mondes 7, 1857, pp. 690f.), and British diplomats also felt a lack of support from their colleagues in Iran. The Russians considered British action in Persia in this period as deliberate aggression, and concern over British expansionist plans was felt by Russian diplomats at all levels, as well as by local civil and military authorities in the Caucasus (Bushev, Gerat, pp. 23f.).

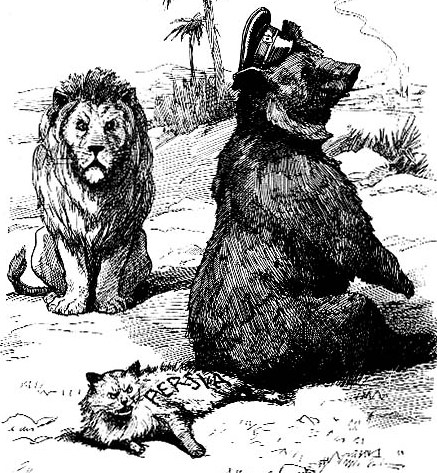

![Cartoon of Persia 1911]() In a tight spot: British 1911 cartoon showing Iran (as the Persian cat) caught between the British lion and the Russian bear who sits on the (unfortunate) “Persian Cat” (Source: The Federalist). The social and geopolitical impact of Iran’s military defeats in the 19th century resonate to this day.

In a tight spot: British 1911 cartoon showing Iran (as the Persian cat) caught between the British lion and the Russian bear who sits on the (unfortunate) “Persian Cat” (Source: The Federalist). The social and geopolitical impact of Iran’s military defeats in the 19th century resonate to this day.

Bibliography

See also: 1. Unpublished official documents: Public Record Office (mainly FO/60 series); India Office Library and Records (mainly Factory Records for Persia and Board’s Drafts); National Record Office of Scotland (private papers of Hon. C. A. Murray, GD/261).

2. Published documents, other sources and studies: P. P. Bushev, “Angliĭskaya agressiya v Irane v 1855-1857,” Kratkie soobshcheniya Instituta vostokovedeniya, Akademiya nauk SSSR, Moscow, 8, 1953, pp. 21-26.

Idem, “Angliĭskaya voennaya ekspeditsiya v Akhvaz,” ibid., 29, 1956, pp. 65-71.

Correspondence Respecting Relations with Persia, London, 1857.

B. English, John Company’s Last War, London, 1971.

ʿA. Farrāšbandī, Ḥamāsa-ye marzdārān-e ǰonūbī-e Īrān, Tehran, 1357 Š./1978.

Idem, Jang-e Engelīs o Īrān dar sāl-e 1273 h.q., Tehran, 1358 Š./1979.

Farroḵ Khan Amīn-al-dawla, Maǰmūʿa-ye asnād o madārek-e Farroḵ Ḵān Amīn-al-dawla, ed. K. Eṣfahānīān and Q. Rowšānī, I, Tehran, 1346 Š./1967.

A. Kasravī, “Jang-e Īrān o Engelīs dar Moḥammera,” Čand tārīḵa, Tehran, 1324 Š./1945, pp. 6-80.

Reżā-qolī Khan Hedāyat, Rawżat al-ṣafā-ye Nāṣerī X, Tehran, 1339 Š./1960.

Moḥammad-Taqī Sepehr, Nāseḵ al-tawārīḵ, ed. J. Qāʾem-maqāmī, Tehran, 1337 Š./1958, pp. 231f.

A. Ṭāherī, Tārīḵ-e rawābeṭ-e bāzargānī o sīāsī-e Īrān o Engelīs II, Tehran, 1356 Š./1977.