The article below is by Professor Ernest Tucker and was originally posted in the Encyclopedia Iranica . on August 15, 2006. Kindly note that version printed below is different in that in the Encyclopedia Iranica in that it has pictures, maps and captions not seein in the Encyclopedia Iranica version.

Readers are also invited to consult Professor Michael Axworthy’s excellent book entitled:

Title: The Sword of Persia: Nadir Shah from Tribal warrior to Conquering Tyrant.

Publisher: I.B. Taurus Publishers, 2009.

ISBN-10: 9781845119829

ISBN-13: 978-1845119829

=========================================================================

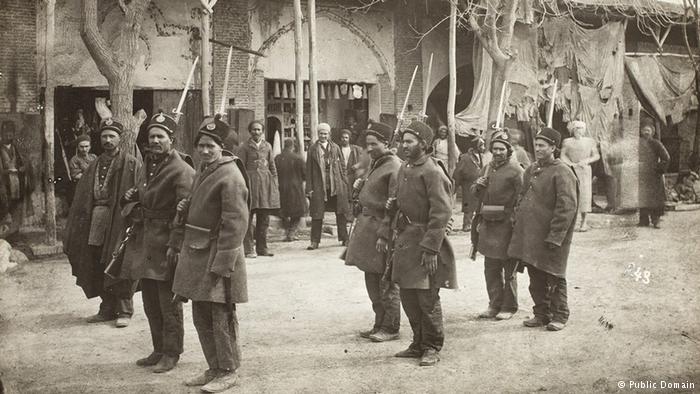

Nader Shah was the ruler of Iran in 1736-47. He rose from obscurity to control an empire that briefly stretched across Iran, northern India, and parts of Central Asia. He developed a reputation as a skilled military commander and succeeded in battle against numerous opponents, including the Ottomans and the Mughals. During Nāder’s campaign in India, and several years after he had replaced the last Safavid ruler on the Persian throne, the elimination of much of the Safavid family effectively ended any real possibility of a Safavid restoration. The decade of Nāder’s own tumultuous reign was marked by conflict, chaos, and oppressive rule. Nāder’s troops assassinated him in 1747, after he had come to be regarded as a cruel and capricious tyrant. His empire quickly collapsed, and the resulting fragmentation of Iran into several separate domains lasted until the rise of the Qajars decades later.

Statue of Nader Shah Afshar in Mashhad, the provincial capital of Khorasan. Nader Shah’s tomb restoration project was led by Houshang Seyhoun in the 1950s, with the 6.5-meter statue being sculpted by Abolhasan Seddighi. The latter reconstructed Nader’s face and features in accordance with historical illustrations. The sculpting process took place in the Borooni workshop supervised by the Italian Embassy in Tehran (Picture source: Kaveh Farrokh’’s lectures at the University of British Columbia’s Continuing Studies Division and Stanford University’s WAIS 2006 Critical World Problems Conference Presentations on July 30-31, 2006).

Born in November 1688 into a humble pastoral family, then at its winter camp in Darra Gaz in the mountains north of Mashad, Nāder belonged to a group of the Qirqlu branch of the Afšār (q.v.) Turkmen. Beginning in the 16th century, the Safavids had settled groups of Afšārs in northern Khorasan to defend Mashad against Uzbek incursions.

The first major international political event that directly affected Nāder’s career was the Afghan invasion of Iran in the summer of 1719 that resulted in the capture of Isfahan and deposition of Shah Solṭān Ḥosayn, the last Safavid monarch, by the autumn of 1722. After the fall of Isfahan, Safavid pretenders emerged all over Iran. One was Solṭān Ḥosayn’s son Ṭahmāsb, who escaped to Qazvin, where he was proclaimed Shah Ṭahmāsb II. He led a resistance movement against the Afghans during the 1720s. The Russians and Ottomans saw the Afghan conquest as their own opportunity to acquire territory in Iran, so both invaded and occupied some land in 1723. The following year they signed a treaty in which they recognized each other’s territorial gains and agreed to support the restoration of Safavid rule.

The Shamshir sword attributed to Nader Shah presently housed in the Nader Museum of Mashad (Muzeye Naderi ye Mashad) [Click to enlarge]. Picture Source: Khorasani, Manouchehr, Arms and Armour from Iran: The Bronze Age to the end of the Qajar Period, Legat Verlag, 2006, pp.483.

Around this time, Nāder began his career in Abivard, an Afšār-controlled town just north of Mashad. He made himself so useful to the local ruler Bābā ʿAli Beg that he gave Nāder two of his daughters in marriage. Due to internal tribal rivalries, Nāder was not able to become Bābā ʿAli’s successor, so he vied for power with various upstart military chiefs in northeastern Iran who had emerged in the wake of the Afghan invasion.

In the mid 1720s, Nāder played an important role in defeating Malek Maḥmud Sistāni, one of that area’s main warlords, who had set himself up as the scion of the 9th-10th century Saffarid dynasty. Nāder was his ally for a while but soon turned against him. His role in suppressing this usurper brought him to Ṭahmāsb’s attention. Ṭahmāsb chose him as his principal military commander to replace Fatḥ ʿAli Khan Qajar (d. 1726, q.v.), whose descendants (the founders of the Qajar dynasty) blamed Nāder for the murder of their ancestor.

With this promotion, Nāder assumed the title Ṭahmāsb-qoli (servant of Ṭahmāsb). His prestige steadily increased as he led Ṭahmāsb’s armies to numerous victories. He first defeated the Abdāli (later known as Dorrāni; q.v.) Afghans near Herat in May 1729, then achieved victory over the Ḡilzi (q.v.) Afghans led by Ašraf at Mehmāndust on 29 September 1729. After this battle, when Ašraf fled from Isfahan to Qandahar, Ṭahmāsb became finally established in Isfahan (with Nāder in actual control of affairs) by December 1729, marking the real end of Afghan rule in Iran. In the wake of Ašraf’s defeat, many Afghan soldiers joined Nāder’s army and proved helpful in many subsequent battles.

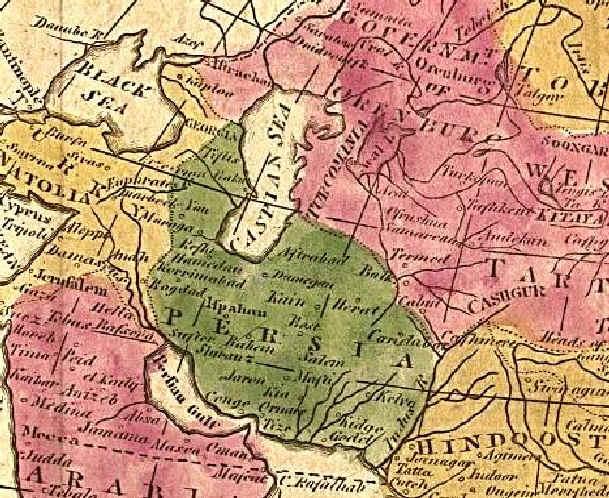

Map of Nader Shah’s empire [Click to Enlarge], just prior to the invasion of India. Picture Source, Farrokh, Kaveh, Iran at War: 1500-1988, Osprey Publishing, pp. 86.

Three months before the Mehmāndust victory, Nāder had sent letters to the Ottoman Sultan Aḥmad III (r. 1703-30) to ask for help, since Ṭahmāsb “was made the legitimate successor of his esteemed father [Solṭān Ḥosayn]” (Nāṣeri, p. 210). Receiving no response, Nāder attacked the Ottomans as soon as Ašraf was defeated and Isfahan reoccupied. He waged a successful campaign during the spring and summer of 1730 and recaptured much territory that the Ottomans had taken in the previous decade. But, just as the momentum of his offensive was building, news came from Mashad that the Abdāli Afghans had attacked Nāder’s brother Ebrāhim there and pinned him down inside the city’s walls. Nāder rushed to relieve him. (This distraction came at just the right time for the Ottomans, since in Istanbul the Patrona Halil rebellion, which led to the deposition of Aḥmad III, broke out in September 1730.) Nāder arrived in Mashad in time to attend the wedding of his son Reżā-qoli to Ṭahmāsb’s sister Fāṭema Solṭān Begum.

Nāder spent the next fourteen months subduing Abdāli forces led by Allāh-Yār Khan. To commemorate his victory over them, he endowed in Mashad a waqf (pious foundation) at the shrine (see ĀSTĀN-E QODS-E RAŻAWI) of Imam ʿAli al-Reżā (d. ca. 818, q.v.). Nāder’s personal seal, preserved on the waqf deed of June 1732, showed his unremarkable Shiʿite loyalty at that time: Lā fatā illā ʿAli lā sayf illā Ḏu’l-Faqār / Nāder-e ʿaṣr-am ze loṭf-e Ḥaqq ḡolām-e hašt o čār (There is no youth more chivalrous than ʿAli, no sword except Ḏu’l-Faqār (q.v.) / I am the rarity of the age, and by the grace of God, the servant of the Eight and Four [i.e., the Twelve Imams].” (Šaʿbāni, p. 375; cf. Rabino, p. 53). Ṭahmāsb took Nāder’s absence in Khorasan as his own chance to attack the Ottomans and pursued a disastrous campaign (January 1731–January 1732), in which the Ottomans actually reoccupied much of the territory recently lost to Nāder. Sultan Maḥmud I (r. 1730-54) negotiated with Ṭahmāsb a peace agreement that allowed the Ottomans to retain these lands, while returning Tabriz to avoid angering Nāder. Three weeks later, Russia and Persia signed the Treaty of Rašt, in which Russia, trying to curry favor with Persia against the Ottomans, agreed to withdraw from most of the Iranian territory it had annexed in the 1720s.

When Nāder learned that Ṭahmāsb had relinquished substantial territory to the Ottomans, he quickly returned to Isfahan. He used the peace treaty as an excuse to remove Ṭahmāsb from the throne in August 1732 and replace him with Ṭahmāsb’s eight-month-old son, who was given the regnal name ʿAbbās III. Now regent, Nāder resumed hostilities against the Ottomans. After a decisive round of victories, interspersed with short excursions to quell uprisings in Fārs and Baluchistan, he signed a new treaty in December 1733 with Aḥmad Pasha, the Ottoman governor of Baghdad. It marked an attempt to reinstate the provisions of the 1049/1639 Ottoman-Safavid Treaty of Qaṣr-e Širin (Ḏohāb), since it called for the restoration of the borders stipulated at that time, a prisoner exchange, and Ottoman protection for all Persian ḥajj pilgrims. The Ottoman sultan would not ratify it, because disputes persisted over control of parts of the Caucasus, and so intermittent hostilities continued.

In March 1734, Šāhroḵ was born to Reżā-qoli and Fāṭema Begum. Šāhroḵ thus formed a direct link between the lineages of Nāder and the Safavids—an important basis for Šāhroḵ’s eventual right to rule. The choice to name his grandson after Šāhroḵ b. Timur (r. 1409-47) revealed Nāder’s growing interest in emulating the conqueror Timur (r. 1369-1405).

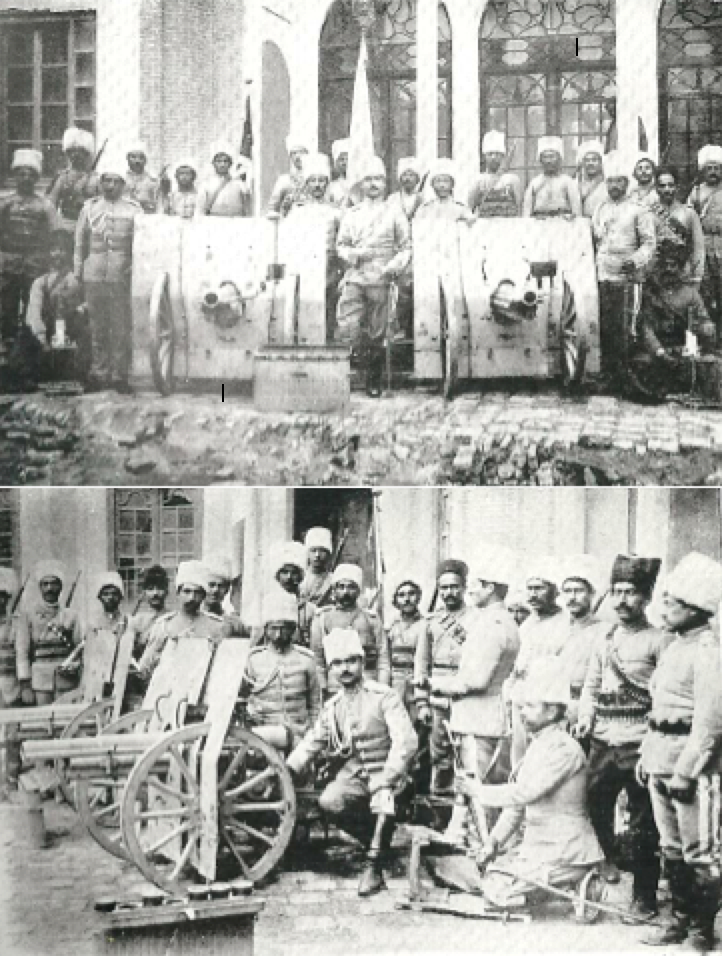

A recreation of a Zanbourak camel artillery unit during the 2,500 year celebrations held in Persepolis in 1971 [Click to enlarge]. Picture Source: Booklet of 2,500 Year Celebrations in 1971

There followed another series of Ottoman-Persian battles in the Caucasus, and Nāder’s capture of Ganja (q.v.), during the siege of which Russian engineers provided assistance. Russia and Persia then signed a defensive alliance in March 1735 at Ganja. In the treaty, the Russians agreed to return most of the territory conquered in the 1720s. This agreement shifted the regional diplomatic focus to a looming Ottoman-Russian confrontation over control of the Black Sea region and provided for Nāder a military respite on his western border.

By the end of 1735, Nāder felt that he had gained enough prestige through a series of victories and had secured the immediate military situation well enough to assume the throne himself. In Feburary 1736, he gathered the nomadic and sedentary leaders of the Safavid realm at a vast encampment on the Moḡān steppe. He asked the assembly to choose either him or one of the Safavids to rule the country. When Nāder heard that the molla-bāši (chief cleric) Mirzā Abu’l-Ḥasan had remarked that “everyone is for the Safavid dynasty,” he was said to have had that cleric arrested and strangled the next day (Lockhart, p. 99). After several days of meetings, the assembly proclaimed Nāder as the legitimate monarch.

The newly appointed shah gave a speech to acknowledge the approval of those in attendance. He announced that, upon his accession to the throne, his subjects would abandon certain religious practices that had been introduced by Shah Esmāʿil I (r. 1501-24) and had plunged Iran into disorder, such as sabb (ritual cursing of the first three caliphs Abu Bakr, ʿOmar, and ʿOṯmān, termed “rightly guided” by the Sunnites) and rafż (denial of their right to rule the Muslim community). Nāder decreed that Twelver Shiʿism would become known as the Jaʿfari madòhab (legal school) in honor of the sixth Imam Jaʿfar al-Ṣādeq (d. 765), who would be recognized as its central authority. Nāder asked that this madòhab be treated exactly like the four traditionally recognized legal schools of Sunnite Islam. All those present at Moḡān were required to sign a document indicating their agreement with Nāder’s ideas.

Flintlock muskets were introduced into Iran during the Afšārid period. Iranian-built flintlock musket of the Afsharid- Qajar type [A] and the barrel of an Iranian flintlock shaped like a dragon’s head with two red stones serving as the “eyes” of that dragon![B] (Picture Source: Khorasani, Maouchehr, Mosthagh (2009), Pistols and Gun Accessories in iran. Classic Arms and Militaria, pp. 23-24).

Just before his actual coronation ceremony on 8 March 1736, Nāder specified five conditions for peace with the Ottoman empire (Astarābādi, p. 286),most of which he continued to seek over the next ten years. They were: (1) recognition of the Jaʿfari maḏhab as the fifth orthodox legal school of Sunnite Islam; (2) designation of an official place (rokn) for a Jaʿfari imam in the courtyard of the Kaʿba [Perry, 1993, p. 854 and “Kaʿba,” in EI2 IV, p. 318 vs. Lockhart, p. 101] analogous to those of the Sunnite legal schools; (3) appointment of a Persian pilgrimage leader (amir al-ḥajj); (4) exchange of permanent ambassadors between Nāder and the Ottoman sultan; and (5) exchange of prisoners of war and prohibition of their sale or purchase. In return, the new shah promised to prohibit Shiʿite practices objectionable to the Ottoman Sunnites

Nāder tried to redefine religious and political legitimacy in Persia at symbolic and substantive levels. One of his first acts as shah was to introduce a four-peaked hat (implicitly honoring the first four “rightly-guided” Sunni caliphs), which became known as the kolāh-e Nāderi (EIr. X, p. 797, pl. CXIII), to replace the Qezelbāš turban cap (Qezelbāš tāj; EIr. X, p. 788, pl. C), which was pieced with twelve gores (evocative of the twelve Shiʿite Imams) Soon after his coronation, he sent an embassy to the Ottomans (Maḥmud I, r. 1730-54) carrying letters in which he explained his concept of the “Jaʿfari maḏhab” and recalled the common Turkmen origins of himself and the Ottomans as a basis for developing closer ties.

During this negotiation and subsequent ones, the Ottomans rejected all proposals related to Nāder’s Jaʿfari maḏhab concept but ultimately agreed to Nāder’s demands concerning recognition of a Persian amir al-ḥajj, exchange of ambassadors, and that of prisoners of war. These demands paralleled the provisions of a long series of Ottoman-Safavid agreements, especially an accord, drawn up in 1727 but never signed, between the Ottoman sultan and Ašraf, the Ḡilzay Afghan ruler of Persia (r. 1725-29). At the end of the 1148/1736 negotiations, both sides approved a document that mentioned only the issues of the ḥajj pilgrimage caravan, ambassadors, and prisoners because of disagreement over the Jaʿfari maḏhab concept. Although no actual peace treaty was signed at that time, mutual acceptance of these other points became the basis for a working truce that lasted several years.

Nāder departed substantially from Safavid precedent by redefining Shiʿism as the Jaʿfari maḏhab of Sunni Islam and promoting the common Turkmen descent of the contemporary Muslim rulers as a basis for international relations. Safavid legitimacy depended on the dynasty’s close connection to Twelver Shiʿism as an autonomous, self-contained tradition of Islamic jurisprudence as well as the Safavids’ alleged descent from the seventh Imam Musā al-Kāżem (died between 779 and 804). Nāder’s view of Twelver Shiʿism as a mere school of law within the greater Muslim community (umma)glossed over the entire complex structure of Shiʿite legal institutions, because his main goal was to limit the potential of Sunnite-Shiʿite conflict to interfere with his empire-building dreams. The Jaʿfari maḏhab proposal also seems intended as tool to smooth relations between the Sunni and Shiʿite components of his own army. In addition, the proposal had economic implications, since control of a ḥajj caravan would have provided the shah with access to the revenue of the lucrative pilgrimage trade.

The military camp of Nader Shah. A detailed diagram of Nader Shah’s military camp by Bazin, The camp market can be seen at the bottom, the Divankhaneh (grand audience hall) tent in the center and the circular harem tent at the top. The 12-striped banner can be seen to the lower left. Picture Source: Matofi, A. (1999). Tarikh e Chahar Hezar Saleye Artesh e Iran: Jled e Dovoom [The Four Thousand Year History of the Iranian Army: Volume Two], Tehran: Iman Publications, pp.-834.

Nāder’s focus on common Turkmen descent likewise was designed to establish a broad political framework that could tie him, more closely than his Safavid predecessors, to both Ottomans and Mughals. When describing Nāder’s coronation, Astarābādi called the assembly on the Moḡān steppe a quriltāy, evoking the practice of Mughal and Timurid conclaves that periodically met to select new khans. In various official documents, Nāder recalled how he, Ottomans, Uzbeks, and Mughals shared a common Turkmen heritage. This concept for him resembled, in broad terms, the origin myths of 15th century Anatolian Turkmen dynasties. However, since he also addressed the Mughal emperor as a “Turkmen” ruler, Nāder implicitly extended the word “Turkmen” to refer, not only to progeny of the twenty-four Ḡozz tribes, but to Timur’s descendants as well.

Nāder’s novel concepts regarding the Jaʿfari maḏhab and common “Turkmen” descent were directed primarily at the Ottomans and Mughals. He may have perceived a need to unite disparate components of the omma against the expanding power of Europe at that time, however different his view of Muslim unity was from later concepts of it. But both ideas had less domestic importance. On coins and seals, and in documents issued to his subjects, Nāder was more conservative in his claim to legitimacy. For example, the distich on one of his official seals focused only on the restoration of stability: Besmellāh – nagin-e dawlat-e din rafta bud čun az jā / be-nām-e Nāder Irān qarār dād Ḵodā (In the name of God – when the seal of state and religion had disappeared from Iran / God established there order in the name of Nāder; Rabino, p. 52). In a proclamation sent to the ulamaof Isfahan soon after the coronation, the Jaʿfari maḏhab was depicted as nothing more than an attempt to keep peace between Sunnites and Shiʿites. The document explained that ʿAli would continue to be venerated as one especially beloved by God, although henceforth the Shiʿite formula ʿAli wali Allāh (ʿAli is the deputy of God) would be prohibited. In contrast to the shah’s letters to foreign rulers, this proclamation did not even mention the Safavids (Qoddusi, p. 540).

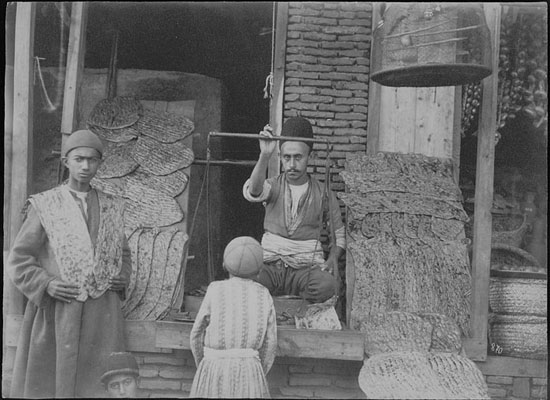

Nāder’s domestic policies introduced major economic, military, and social changes. He ordered a cadastral survey in order to produce the land registers known as raqabat-e Nāderi. Because of the establishment of the Jaʿfari maḏhab, the Safavid framework of pious foundations was suspended (Lambton, p. 131), although their revenues were the main source of financial support for important ulama. Only in the last year of his reign did Nāder decree the resumption of pious foundations. After his accession to the throne, Nāder claimed the ruler’s privilege to issue coinage in his name. His monetary policy linked the Persian currency system to the Mughal system, since he discontinued the Safavid silver ʿAbbāsi and minted a silver Nāderi whose weight standard corresponded with the Mughal rupee (Rabino, p. 52; see COINS AND COINAGE, in EIr. VI, p. 35). Nāder also attempted to promote fixed salaries for his soldiers and officials instead of revenues derived from land tenure. Continuing a shift that had begun in the late Safavid era, he increased substantially the number of soldiers directly under his command, while units under the command of provincial and tribal leaders became less important. Finally, he continued and expanded the Safavid policy of a forced resettlement of tribal groups (Perry, 1975, pp. 208-10).

Nader Shah defeating Ashraf the Afghan as seen in the Jahangoshay-e Naderi. Note that the Afghan attacks are repelled by a disciplined row of Iranian artillery. The Afghans soon tried to copy Nader Shah’s tactics but this failed to save them from complete defeat in Iran. Note that the infantry stand behind the cannon, ready to deploy when Nader gives the order. There is a space after the first two cannon (from the bottom of the picture) where Nader’s cavalry stand ready for the counterattack. The cavalryman to the front is depicted with mail, Kolah-Khud helmet and the Shamshir sword. Picture Source, Farrokh, Kaveh, Iran at War: 1500-1988, Osprey Publishing, pp. 86.

All these reforms can be viewed as attempts to address weaknesses that had emerged in the late Safavid era, but none solved the problems that were tied to larger trends in the world economy. Iran had suffered from a swift rise in the popularity of Indian silk in Europe during the last few decades of Safavid rule, a shift that dramatically reduced Iran’s foreign income and indirectly contributed to the draining of bullion away from Persian state treasuries (Matthee, pp. 13, 67-68, 203-06, 212-218). This crisis, in turn, put more pressure on the provinces to produce tax revenue, which led provincial governors to take oppressive measures and fueled the Afghan revolt that had resulted in the Safavid collapse in the first place.

After his ascension to the throne Nāder’s main military task was the ultimate defeat of the remaining Afghan forces that had ended Safavid rule. After laying siege to Qandahar for almost a year, Nāder destroyed it in 1738—the last redoubt of the Ḡilzi, who were led by Shah Ḥosayn Solṭān, the brother of Shah Maḥmud, who had been the first Ḡilzay to rule Persia (1722-1725). On the site of his camp Nāder built a new city, Nāderābād, to which he transferred Qandahar’s population and Abdāli Afghans.

The destruction of Qandahar completed the reconquest of territory lost since the reign of Shah Solṭān Ḥosayn. Nāder’s career now entered a new phase: the invasion of foreign territory to pursue dreams of a world empire that could resemble the domains of Chinghis Khan (d. 1227, see ČENGIZ) and Timur. After the fall of Qandahar, many Afghans joined his army. His pursuit of Afghans who had fled across the Mughal frontier grew into an invasion of India when Nāder accused the Mughals of providing them with shelter and aid. Nāder had appointed Reżā-qoli as his deputy in Iran. While his father was away, Reżā-qoli feared a pro-Safavid revolt and had Moḥammad Ḥasan (the leader of the Qajars between 1726 and 1759) execute Ṭahmāsb and his sons.

After a successful offensive that culminated in the final defeat of the Mughal forces at the battle of Karnāl near Delhi in February 1739, Nāder made the Mughal emperor Moḥammad Šāh (r. 1719-48) his vassal and divested him of a large part of his fabulous riches, including the Peacock Throne and the Koh-i-Noor (q.v.) diamond. When the rumor spread that Nāder had been assassinated, the Indians attacked and killed his troops. In retaliation, Nāder gave his soldiers permission to plunder Delhi and massacre its inhabitants. The peace treaty restored control of India to Moḥammad Šāh under Nāder’s distant suzerainty; it proclaimed M oḥammad Šāh’s legitimacy, citing the Turkmen lineage that he shared with Nāder (Astarābādi, p. 327). Nāder arranged a ceremony in which he placed the crown back on Moḥammad Shah’s head. To further emphasize Moḥammad Šāh’s subordinate status, he assumed the title šāhānšāh. To further strengthen his ties to the Mughals, Nāder married his son Naṣr-Allāh to a great granddaughter of the Mughal emperor Awrangzēb (r. 1658-1707). His chroniclers represent his victory over Moḥammad Šāh as another sign of his similarity to Timur. The shah himself was so obsessed with emulating Timur that he moved, for a time, to Mashad (Lockhart, pp. 188-89, note 4).

Painting of the Battle of Karnal made by Mosavar ol-Mamalek [Click to enlarge]. Picture Source: R. Tarverdi (Editor) & A. Massoudi (Art editor), The land of Kings, Tehran: Rahnama Publications, 1971, p.228.

While Nāder was invading India, Reżā-qoli was securing more territory for Nāder north of Balḵ and south of the Oxus river. His campaign aroused the ire of Ilbars, the khan of Khwarazm (see CHORASMIA, in EIr. V, p. 517), and of Abu’l-Fayż (r. 1711-47), the Toqay-Timurid khan of Bukhara (see BUKHARA, in EIr. IV, p. 518). When they threatened counterattacks, Nāder engaged in a swift campaign against them on his way back from India. He executed Ilbars and replaced him with a more compliant ruler, but this new vassal would soon be overthrown. Abu’l–Fayż, like the Mughal emperor, accepted his status as Nāder’s subordinate and married his daughter to Nāder’s nephew.

After the campaigns in India and Turkestan, particularly with acquisition of the Mughal treasury, Nāder found himself suddenly wealthy. He issued a decree canceling all taxes in Iran for three years and decided to press forward on several projects, such as creation of a new navy. Nāder had sent his naval commanders at various times on expeditions in the Persian Gulf, particularly to Oman, but these missions were unsuccessful, in part because it was difficult to secure naval vessels of good quality and in adequate numbers. In the summer of 1741, Nāder began to build ships in Bušehr, arranging for lumber to be carried there from Māzāndarān at great trouble and expense. The project was not completed, but by 1745 he had amassed a fleet of about thirty ships purchased in India (Lockhart, p. 221, n. 3).

However, Nāder experienced several major setbacks after his return to Iran. In 1741-43 he launched a series of quixotic attacks in the Caucasus against the Dāḡestānis (see DĀḠESTĀN, in EIr. VI, p. 570-71) in retaliation for his brother’s death. In 1741, an attempt was made on Nāder’s life near Darband. When the would-be assassin claimed that he had been recruited by Reżā-qoli, the shah had his son blinded in retaliation, an act for which he later felt great remorse. Marvi reported that Nāder began to manifest signs of physical deterioration and mental instability. Finally, the shah was forced to reinstate taxes due to insufficient funds, and the heavy levies sparked numerous rebellions.

In spite of mounting problems, in 1741 Nāder sent an embassy to the Ottomans to resubmit his 1736 proposal for a peace treaty. But Maḥmud I had just won wars against Russia and Austria and was not receptive. The sultan rejected the shah’s claim to Iraq (a claim based on Timur’s earlier control of the province). Then the Ottomanlegal authority, the šayḵ al-Eslām, issued a fatwā (legal opinion) formally declaring the Jaʿfari maḏhab heretical. In response, Nāder besieged several cities in Iraq in 1743, with no results, and in December of that year he signed a ceasefire with Aḥmad Pāšā, the Ottoman governor of Baghdad (d. 1747; cf. EI2 I, p. 291). Subsequently, Nāder convened a meeting of ulama from Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, and Central Asia in Najaf at the shrine of ʿAli b. Abi Ṭāleb (d. 661, q.v.), the fourth of the Rightly-Guided Caliphs and the first Imam. After several days of lively debate on the question of the Jaʿfari maḏhab, the participants signed a document which recognized the Jaʿfari maḏhab as a legitimate legal school of Sunnite Islam. The Ottoman sultan, however, remained unimpressed by this outcome.

Nāder soon had to leave Iraq to suppress several domestic rebellions. The most serious of these began near Shiraz in January 1744 and was led by Moḥammad Taqi Khan Širāzi, the commander of Fārs province and one of Nāder’s favorites. In June 1744, Nāder sacked Shiraz, and by winter he had crushed these revolts. He resumed his war against the Ottomans and defeated them in August 1745 at Baḡāvard near Yerevan. Although Nāder’s victory led to new negotiations, his bargaining position was not strong because of new, large-scale domestic uprisings. The shah dropped his demands for territory and for recognition of the Jaʿfari maḏhab, and the final agreement was based only on the long mutually acceptable positions regarding frontiers, protection of pilgrims, treatment of prisoners, and exchange of ambassadors (Lockhart, p. 255). The agreement recognized the shared Turkmen lineage and ostensibly proclaimed the conversion of Iran to Sunnism. Yet the necessity to guarantee the safety of pilgrims to the Shiʿite shrines (ʿatabāt-e ʿāliya) in Iraq reveals the formal character of this concession. The treaty was signed in September 1746 in Kordān, northwest of Tehran. It made possible the official Ottoman recognition of Nāder’s rule, and the sultan dispatched an embassy with a huge assortment of gifts in the spring of 1747, although the shah did not live to receive it.

One of Nader Shah’s musketeers armed also with Shamshir sword and Khanjar dagger. .He also carries a powder flask. Picture Source: Booklet of 2,500 Year Celebrations in 1971

Nāder had spent the winter and spring of 1746 in Mashad, where he formulated a strategy to suppress the plethora of internal revolts. He also oversaw the construction of a treasure house for his Indian booty at nearby Kalāt-e Nāderi (see EI2 V, p. 103). The building complex that Nāder constructed within this natural mountain fortress, near his birthplace in northern Khorasan, became his designated retreat, and he created there a secure showplace for his accomplishments. Nāder followed the nomadic custom of not staying long in any permanent capital city, and Kalāt and Mashad (in, as he saw it. a complementary relationship) served as his main official sites in ways that resembled capital cities of other nomadic empires. Under Nāder’s patronage, Mashad flourished at the midpoint of a trading route between India and Russia and grew in importance as a major pilgrimage center with its Emam Reẓā shrine complex.

In June 1747, a cabal of Afšār and Qajar officers succeeded in killing Nāder. The succession struggle embroiled Persia in civil war for the next five years. Two months before the assassination, Nāder’s nephew ʿAli-qoli, son of his brother Ebrāhim (d. 1738), had risen in revolt, and in July he followed his uncle on the throne as ʿĀdel Shah (r. 1747-48). Nāder’s grandson Šāhroḵ, although blinded after an earlier coup attempt, finally secured the throne in Khorasan in 1748 as a vassal of the Afghan Aḥmad Shah Dorrāni (r. 1747-73, q.v.). This former deputy of Nāder founded the Dorrāni dynasty and is credited with being the first ruler of an independent Afghan state. Šāhroḵ ruled for almost fifty years until 1795, when Āqā Moḥammad Khan Qajar (r. 1779-97) deposed him, marking the end of the rule of the Afsharids (q.v.) in Iran.

Bibliography

The following list is a supplement to the extensive bibliography in John R. Perry, “Nādir Shāh Afshār,” in EI2 VII, 1993, p. 856, which itself is an addition to the bibliographies of Vladimir Minorsky (“Nādir Shāh,” in EI1 III, pp. 813-14) and Laurence Lockhart (Nadir Shah: A Critical Study Based Mainly Upon Contemporary Sources, London, 1938, pp. 314-28). It uses Perry’s categories for new materials, yet also includes already known works if cited in this article.

Persian narrative sources.

Mirzā Mahdi Khan Astarābādi (q.v.; more correctly, Estrābādi), Tāriḵ-e jahāngošā-ye nāderi, ed. ʿA. Anvār, Tehran, 1962. Ḵᵛaja ʿAbd-al-Karim Kašmiri, Bayān-e wāqeʿ, ed. K. B. Nasim, Lahore, 1970.

Moḥammad Kāzem Marvi, Tārīḵ-e ʿālam-ārā-ye Nādirī, 3 vols., Tehran, 1364/1985-86.

Moḥammad Reżā Nāṣeri, ed., Asnād o mokātebāt-e tāriḵi-e Irān: I – Dawra-ye afšāriya, Tehran, 1985.

Moḥammad Šāfeʿ Wāred Tehrāni, Tāriḵ-e nāderšāhi, ed. Reżā Šaʿbāni, Tehran, 1990.

Selected non-Persian sources and documents.

Erewants’i Abraham, History of the Wars: 1721-1738, tr. George A. Bournoutian, Costa Mesa, Calif., 1999.

Kretats’i Abraham, The Chronicle of Abraham of Crete, tr. George A. Bournoutian, Costa Mesa, Calif., 1999.

Riazul Islam, A Calendar of Documents on Indo-Persian Relations: 1500-1750, 2 vols., Tehran and Karachi, 1979-82, II, pp. 74-107.

Koca Rağib Mehmed Paşa, Tahkik ve tevfik: Osmanli-Iran diplomtik münasebetlerinde mezhep tartişmalari, ed. Ahmet Zeki Izgöer, Istanbul, 2003; in romanized Ottoman. ʿ

Abd al-Ḥosayn Navāʾi, ed., Nāder Shāh o bāzmāndagānaš: Hamrāh bā nāmahā-ye salṭanati o asnād-e siāsi o edāri, Tehran, 1989.

Moḥammad-Amin Riāḥi, ed., Safarāt-nāmahā-ye Irān: Gozarešhā-ye mosāfarat o maʾmuriyat-e sāferan-e ʿoṯmāni dar Irān, Tehran, 1989, pp. 205-42.

Studies not mentioned in other articles.

Chahryar Adle, “La Bataille de Mehmândust (1142 /1729),” Stud. Ir. 2, 1973, pp. 235-41.

Layla S. Diba, “Visual and Written Sources,” in Carol Bier,ed., Woven from the Soul, Spun from the Heart: Textile Art of Safavid and Qajar Iran 16th-19th Centuries, Washington, 1987, pp. 84-97.

Naimur Rahman Farooqi, Mughal-Ottoman Relations: A Study of Political and Diplomatic Relations between Mughal India and the Ottoman Empire 1556-1748, Delhi, 1989; originally, Ph.D. diss., University of Wisconsin–Madison, 1986.

Willem Floor, Ḥokumat-e Nāder Shah: Be rewāyat-e manābeʿ-e holandi, tr. Abu’l-Qāsem Serri, Tehran, 1989.

Idem, “The Iranian Navy in the Gulf during the Eighteenth Century,” Iranian Studies 20, 1987, pp. 31-53.

Vladilen G. Gadzhiev, Razgrom Nadir-shakha v Dagestane (Nāder Shāh’s destruction in Daghestan), Makhachkala (Russian Federation), 1996.

Mohammad Ali Hekmat, Essai sur l’histoire des relations irano-ottomanes de 1722 à 1747, Paris, 1937.

Ann K. S. Lambton, Landlord and Peasant in Persia: A Study of Land Tenure and Land Revenue Administration, London, 1953, pp. 129-33, 164.

Rudolph P. Matthee, The Politics of Trade in Safavid Iran: Silk for Silver 1600-1730, Cambridge, 1999, pp. 175-230.

John Perry, “Forced Migration in Iran during the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries,” Iranian Studies 8, 1975, pp. 199-215.

Moḥammad Ḥosayn Qoddusi, Nāder-nāma, Tehran, 1960.

Hyacinth Louis Rabino di Borgomale, Coins, Medals and Seals of the Shâhs of Îrân, 1500-1941, London, 1945, pp. 51-56; repr., Dallas, 1973.

Reżā Šaʿbāni, Tāriḵ-e ejtemāʿi-ye Irān darʿaṣr-e afšāriya, 2nd. ed., Tehran, 1986.

Manṣur Sefatgol, “Baroftādan-e farmānravāʾi-e Afšāriān az Ḵorāsān va satizahā-ye pāyāni-e Afšāriān ba Qājāriān,” Farhang 9/3, Fall 1375/1996, pp. 293-338.

Ernest Tucker, “Explaining Nadir Shah: Kingship and Royal Legitimacy in Muhammad Kazim Marvi’s Tārīkh-i ʿālam-ārā-yi Nādirī,” Iranian Studies 26, 1993, pp. 95-117.

Idem, “Nadir Shah and the Jaʿfari Madhhab Reconsidered,” Iranian Studies 27, 1994, pp. 163-79. Idem, “The Peace Negotiations of 1736: A Conceptual Turning Point in Ottoman-Persian Relations,” Turkish Studies Association Bulletin 20/1, 1996, pp. 16-37.